I had the good fortune to spend eight days in Malta, most of them in Valletta, its capital. We will need to go back a few years from 1805 to pick up on Nelson’s connection with Malta, but Malta has its own claim to immortal memory. Because of its strategic location, Malta played a starring role in 400 years of Western history, from the Great Siege of 1565 to a second, even longer siege in World War II. The Knights’ victory over the Ottoman Turks and the Maltese/British victory over Hitler and Mussolini were improbable, inspiring and indelible parts of their respective eras.

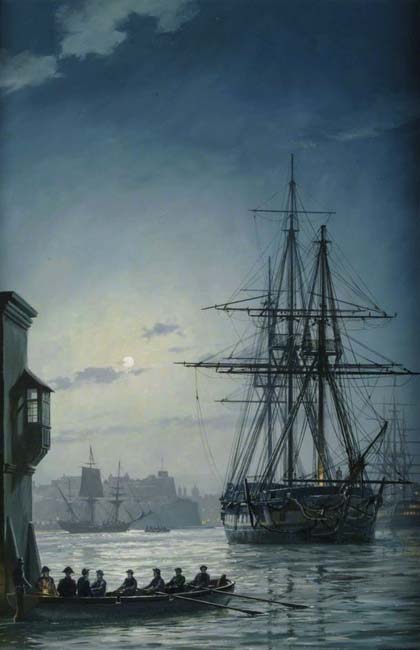

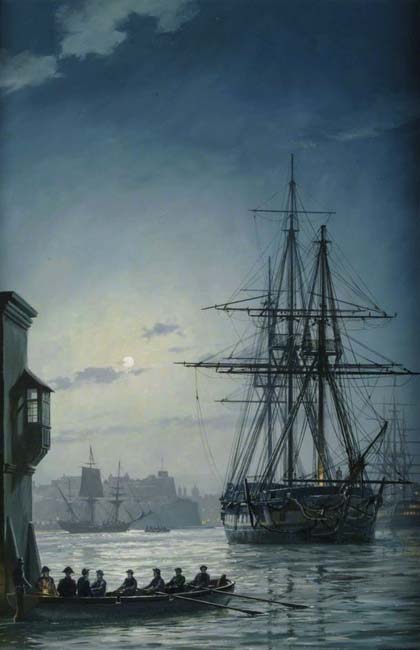

Malta is also the setting for book nine of the Aubrey-Maturin series, and the book begins with O’Brian’s atmospheric description of Malta’s Grand Harbour:

A gentle breeze from the north-east after a night of rain, and the washed sky over Malta had a particular quality in its light that sharpened the lines of noble buildings, bringing out all the virtue of the stone; . . . beyond and below the Baracca there was the vast sweep of the Grand Harbour, pure sapphire today, flecked with the sails of countless small craft plying between Valletta and the great fortified headlands on either side, St. Angelo and Isola, and the men-of-war, the troopships and the victuallers, a sight to please any sailor’s heart.

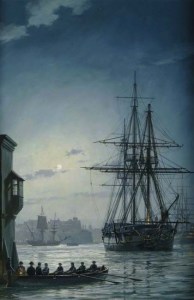

Malta is a symphony of virtuous stone, and Valletta retains its character as a military fortress. Geoff Hunt’s cover for Treason’s Harbour captures this quality, with HMS Surprise in the foreground and St. Angelo looming in the background across the Grand Harbour. St. Angelo became the headquarters for the Knights of Malta when they took over Malta in the early 16th century, and it figured prominently in the defeat of the Ottomans. Eventually it became the headquarters for the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet and held this position, as HMS St. Angelo, until the British departed in 1979. The Maltese government gave St. Angelo back to the Knights after the British left and, judging by the current construction activity, the Knights have plans for their former fortress. Unfortunately, it is now closed to the public, but it still dominates the viewpoint in the Grand Harbour (see above).

Upper Barrakka at Sunrise. This is the gathering place for Valletta, high above the Grand Harbour, and the views are magnificent.

Geoff Hunt’s cover art for Treason’s Harbour

Symbol for the Royal Navy C-in-C Mediterranean, from the Malta Maritime Museum.

Nelson’s connection with Malta begins in 1798, before the Battle of the Nile, when he was chasing Napoleon across the Mediterranean. Faulty intelligence initially led Nelson and the British squadron to Egypt ahead of Napoleon. Napoleon instead was capturing Malta from the Knights, in part for the purpose of financing his expedition and in part to deny it to his enemies. Unfaithful to their martial heritage, the Knights gave up Malta without a fight. After a brief but frenetic stay in Valleta, Napoleon looted Malta and its churches, installed a French military government, and left behind an occupying force. The looting and irreligious revolutionary fervor ultimately proved the French undoing, as it instigated a Maltese revolt and the eventual invitation for the British to come in and help the Maltese eject the French. The Brits accepted the invitation and then stayed another 164 years.

Napoleon and the remainder of his force left Malta for conquests he thought would rival Alexander the Great. He departed with the treasure of Malta stuffed into his flagship, the 118 gun L’Orient. Nelson’s force caught up with the French Fleet in Aboukir Bay, leading to his famous victory at the Battle of the Nile. Napoleon wasn’t present for the battle (he had already landed his army and conquered Egypt), but L’Orient and the Maltese treasure was. During the night action L’Orient blew up in spectacular fashion. Maltese guides to this day talk about recovering the treasure, but as far as I know it has never been found. L’Orient also figures in the immortal memory in a more ironic way. One of Nelson’s captains recovered a mast from L’Orient, fashioned it into a casket, and presented it to Nelson. To this day, Nelson’s body rests in the casket fashioned from L’Orient’s wreckage.

Meanwhile, the Royal Navy began a blockade and siege of the French forces in Malta, led primarily by one of Nelson’s Captains, Alexander Ball, who eventually became the first governor of Malta. Ball himself was one of Nelson’s favorite subordinates and a few weeks before the Nile had saved Nelson and his flagship, HMS Vanguard, through a remarkable feat of seamanship. A storm had dismasted Vanguard and was driving the uncontrollable ship onto the sailors’ dreaded lee shore. Ball rigged a towline and, despite the danger to his own ship, pulled Nelson and the Vanguard to safety (C.S. Forester has Horatio Hornblower accomplish a similar feat in Book II of the Captain Hornblower trilogy, Ship of the Line.)

Back to Malta. Faced with the Maltese revolt, the French withdrew into the Valletta fortress. In his new flagship, HMS Foudroyant, Nelson participated in the blockade and in efforts to bring troops to capture Valletta. That led him to his one trip ashore in Minorca, which we’ll address in a later blog. By this time, however, Nelson’s focus was on Naples and Lady Hamilton. He even left the Mediterranean before Malta fell to the British in September of 1800.

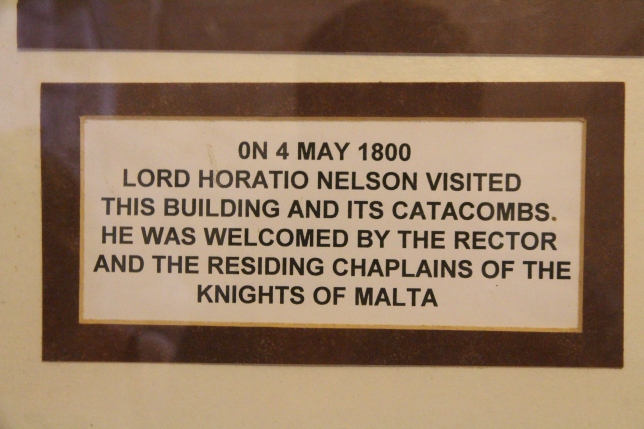

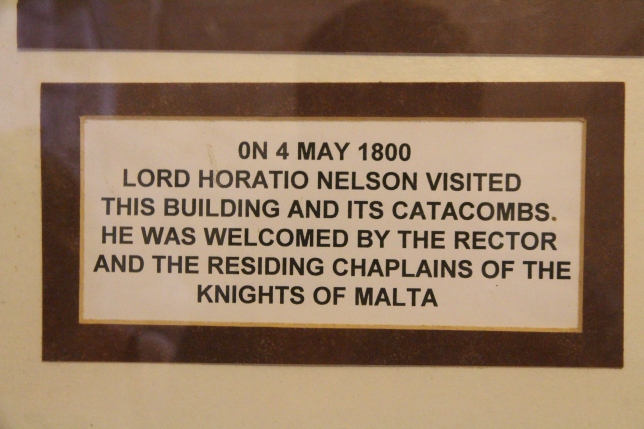

Plaque commemorating Nelson’s visit to St. Paul’s grotto church and catacombs in L-Rabat.

Historians agree that Nelson visited Malta during this time period, but then legend intervenes and injects controversy and doubt. Malta figures prominently in early Christian history, as St. Paul was shipwrecked there and he converted the islanders to Christianity before he was removed to Rome and martyrdom. During his three months on Malta, St. Paul lived and worshiped in the catacombs in L-Rabat, just outside Malta’s former capital-fortress of Mdina. The Knights built a lovely church there to commemorate St. Paul, which I visited during my stay on Malta. Not expecting any Nelson connection, I was surprised to see the plaque indicating that Nelson visited the grotto/catacombs shortly before he left the Mediterranean in 1800. The question is, did Emma Hamilton accompany him and how did they conduct themselves during their visit?

Hamilton’s recent biographer reports that Lord and Lady Hamilton accompanied Nelson to Malta on the Foudroyant in May of 1800 and visited St. Paul’s Bay and Marsa Sirocco Bay (now Marsaxlokk Bay), which are nearby (Valletta was held by the French at the time). Notwithstanding the plaque’s silence on the subject, I conclude that Lady Hamilton must have also been present with Nelson, as they were inseparable at this point (and their daughter, Horatia, was born January 29, 1801). As a interesting coda to Nelson and Emma’s Malta visit, Peter Elliott reports that a bed reputed to have been used by Nelson and Lady Hamilton was one of the “trophies” that had to be disposed of when the British withdrew from Malta in 1979. The bed had apparently been housed in the Captain’s House at Fort St. Angelo, but Elliot also notes that its provenance was Neapolitan — brought to Malta after the capture of Naples in 1943.

St. Paul’s Church in L-Rabat. The same catacombs that sheltered St. Paul sheltered countless Maltese during World War II as air raid shelters. There’s an equally charming yet less historic St. Paul Shipwreck church in Valletta.

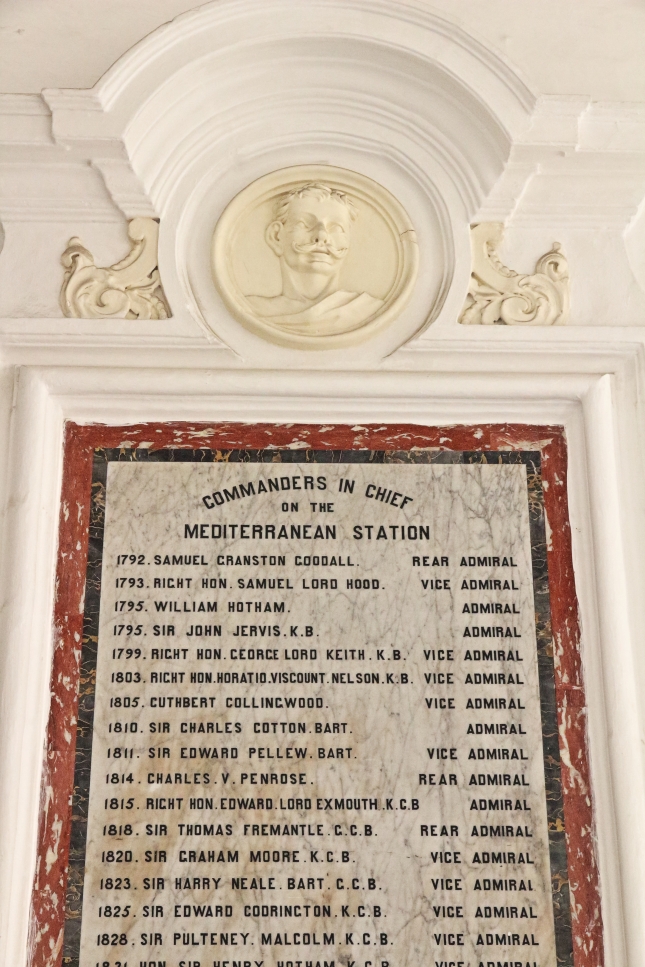

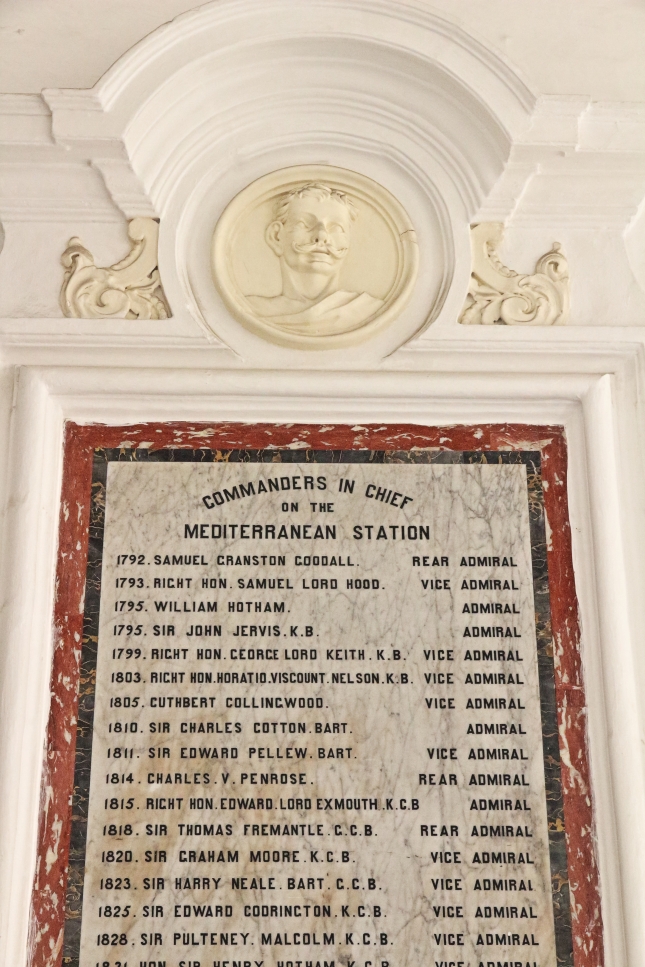

After the Napoleonic Wars, Malta remained a British possession. When the Suez Canal was finished Malta gained importance as a coaling station. Its strategic location astride the trading routes also led it to become the home port for the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet. Fearing French, Italian or other enemies, the British strengthened Malta’s fortifications. A former Valletta palace became Admiralty House, the residence of the C-in-C Mediterranean. It’s a wonderful, airy building that now serves as Malta’s National Gallery of Art. It retains relics of its nautical past, however, including plaques that commemorate all of the admirals who commanded in the Mediterranean. They contain a long list of famous British mariners, including Nelson and Collingwood. I don’t believe either ever took up residence there, however,

Admiralty House Entrance Hall, now the Maltese National Gallery of Art

Partial roster of Mediterranean Station C-in-C’s

Admiralty House ceiling decorations.

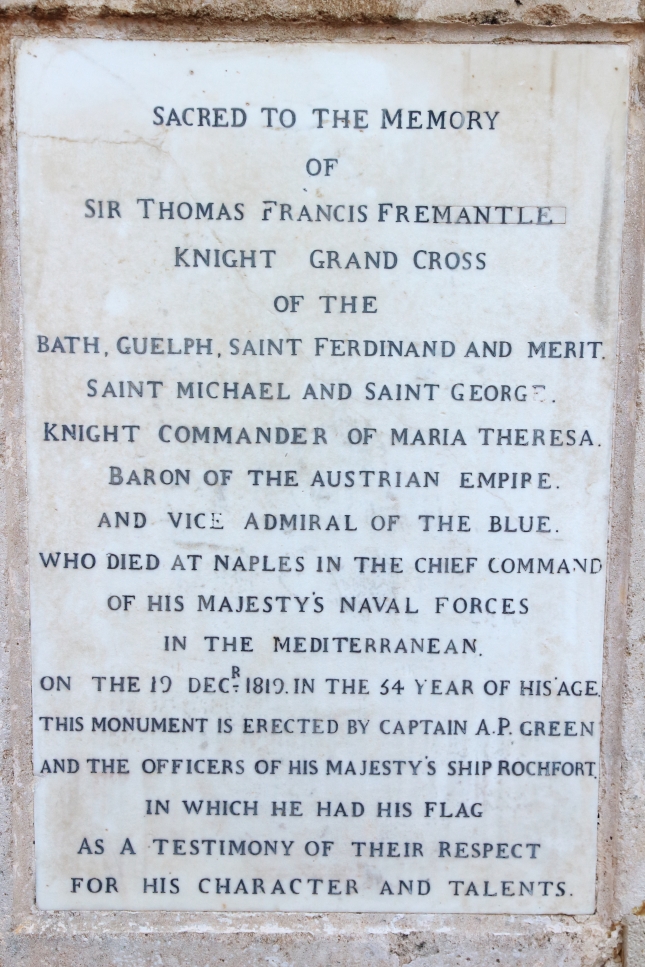

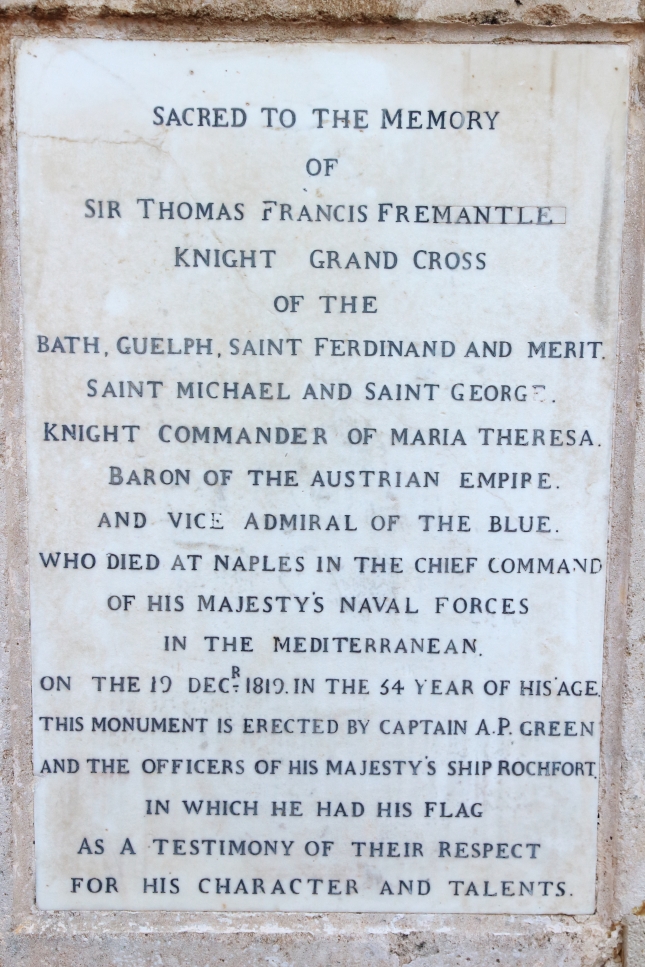

Memorial to Sir Thomas Freemantle at the Upper Barakka. Freemantle was one of Nelson’s “Band of Brothers” and captained HMS Neptune at Trafalgar. He survived the battle and became a rich man from the prize money he gained.

I found Peter Elliott’s, The Cross and the Ensign (1994), in a bookstore during my visit and it details the history of the Royal Navy and Malta from 1798-1979. Elliott does not comment on the coincidence, but he tells the story of one of the more intriguing connections between historical fact and historical fiction. Although Jack Aubrey commands other ships during the course of the series, his favorite ship and most frequent command is HMS Surprise, a sweet-sailing but small 28-gun frigate. O’Brian’s fictional Surprise has a real historical antecedent, but Elliott relates the story of a successor 20th century HMS Surprise. It was a small worship converted into a yacht for the use of the admiral commanding in the Mediterranean. In 1949, then Princess Elizabeth sailed out of Malta on Surprise on a cruise accompanying Earl Mountbatten, who was C-in-C Mediterranean at the time. Accompanying HMS Surprise was HMS Magpie, then under the command of Elizabeth’s husband, the Duke of Edinburgh.

The Royal Navy left Malta in 1979 in a departure full of sadness and ceremony. During those last years of the Cold War Malta’s government tried to be non-aligned and NATO fleets could no longer use its harbors (George H.W. Bush did summit with Gorbachev on Malta in the 80’s). Despite the current lack of any real naval presence (Malta has only a few patrol boats), Malta’s harbors still retain their nautical character. They now mostly feature yachts and cruise ships, which fill Grand Harbour and Marsamsxett. Malta’s famous dockyard still operates, however, and there looked to be substantial commercial activity taking place there.

During my visit I sat on the balcony and watched the boats for hours, envisioning the harbors filled with wooden ships as well as their iron and steel successors. I’ll leave Winston Churchill with the last word. He called Malta “that tiny rock of history and romance.” Churchill probably meant romance of the Walter Scott variety rather than of the Nelson-Hamilton kind, and he must have been thinking about knightly valor, chivalry and the Hospitallers’ faith. Malta’s romance also comes from the sheer notion that such a small place could serve such an outsize role throughout modern Western history.

PS: Nicholas Monserrat’s novel, The Kapillan of Malta, is an indispensable resource for understanding Malta and its character. I recommend it to anyone contemplating a visit.

More virtuous stone — Fort Manoel across Marsamsxett from Valletta

St. Angelo looking towards harbor entrance

Boats in front of Fort Manoel

Valletta from Sliema ferry. Our apartment was just to the right of the church tower.

Water taxi heading back to Victoriosa (Birgu), with St. Angelo in the background

Approaching the Lascaris Bastion and the Upper Barrakka on the water taxi.

Marsamsxett Sunset — a sight to please any sailor’s heart.

Burnham Market is a quaint and affluent town that appears to be a destination for holiday travelers from London and the South. During the bank holiday weekend I was there, they crowded the town and took advantage of an unseasonably clear and hot day. The town is charming. The architectural blend of brick and cobblestone found on many of the local buildings is particularly remarkable, and I found this pattern throughout Norfolk.

Burnham Market is a quaint and affluent town that appears to be a destination for holiday travelers from London and the South. During the bank holiday weekend I was there, they crowded the town and took advantage of an unseasonably clear and hot day. The town is charming. The architectural blend of brick and cobblestone found on many of the local buildings is particularly remarkable, and I found this pattern throughout Norfolk.